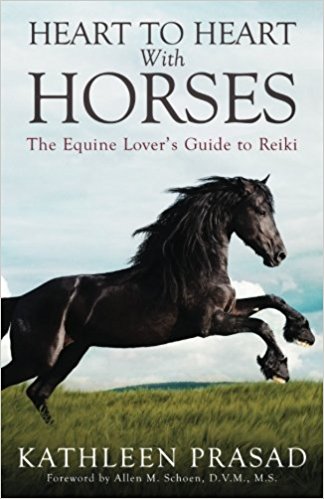

When you don’t know what to do, or even when you do, sometimes the key is simply to be. Author and animal Reiki instructor Kathleen Prasad’s book, Heart to Heart with Horses: The Equine Lover’s Guide to Reiki (2017: Animal Reiki Source), illustrates this beautifully. As one of Kathleen’s students, I was already familiar with her work, but a desire to learn more about working with horses led me to this book, her latest.

When you don’t know what to do, or even when you do, sometimes the key is simply to be. Author and animal Reiki instructor Kathleen Prasad’s book, Heart to Heart with Horses: The Equine Lover’s Guide to Reiki (2017: Animal Reiki Source), illustrates this beautifully. As one of Kathleen’s students, I was already familiar with her work, but a desire to learn more about working with horses led me to this book, her latest.

Reiki, a Japanese stress relief and relaxation technique that also promotes healing, is not limited to hands-on practice, especially with animals. A practitioner can give a Reiki treatment from across the room or just outside an enclosure or stall. It’s all about energy and presence, to which animals are much more attuned than humans. Horses in particular are very intuitive and sensitive creatures. You do not need to use the traditional Reiki hand positions, or use your hands at all, for them to “get it.” In other words, instead of “doing” Reiki, try “being” Reiki, Kathleen suggests, and she offers several ways to do this.

From her own experience and a sprinkling of guest authors’ stories, Kathleen teaches animal Reiki as a meditative practice which creates space for healing … whatever healing might mean for that horse in that moment. The practitioner does not have to know “what’s wrong” or direct how healing will happen. Sharing Reiki energy helps set up the conditions for whatever is needed — the clearing up of an infection, a peaceful transition at the end of life, insight into a behavioral issue, or none of these.

The practitioner’s state of mind and heart is the real key, Kathleen says, and a daily meditation practice helps with this. It’s also important to let the animal choose to participate in the treatment, or not. She says horses will often test the practitioner by declining (moving away or showing signs of irritation or aggravation), just to see if it truly is up to them. Once the horse knows he has a choice (and, I might add, that you are not the sort of healer who pokes, prods, or gives shots), he is more likely to be receptive. A horse may even move closer and position himself near you, perhaps pushing a hip or shoulder into your hands. Then you can offer some gentle hands-on work, but that should always be at the animal’s initiative, Kathleen says.

We humans have ridden horses into battle, made them schlep us and our stuff over great distances, and more. Heart to Heart with Horses offers us a respectful, compassionate way forward — connecting with these magnificent animals and allowing them to be our teachers.

Something in Fredrik Backman’s

Something in Fredrik Backman’s