We were saying our goodbyes outside the restaurant when a train came roaring by. Charlie, then well into his seventies, sprinted across the parking lot for a closer look. Having known him for years, I knew he was taking note of what kind of train it was and its probable route and cargo. He’d be able to tell us its history.

But my partner, Kathy, who’d met him more recently, whirled around and stared after him.

“He’ll be back in a minute,” I said.

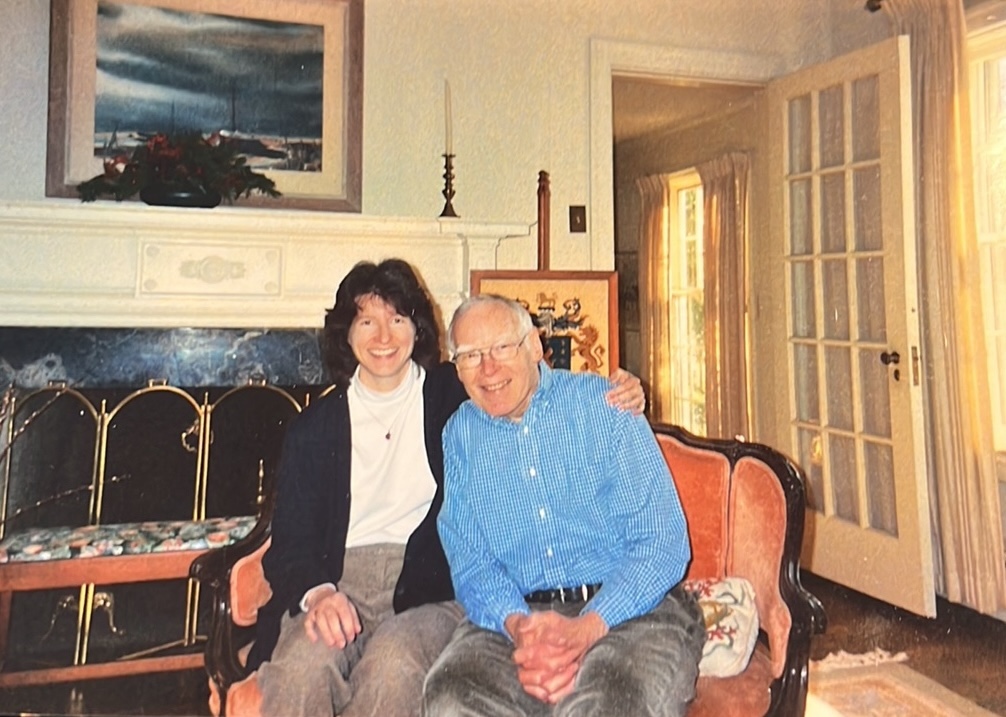

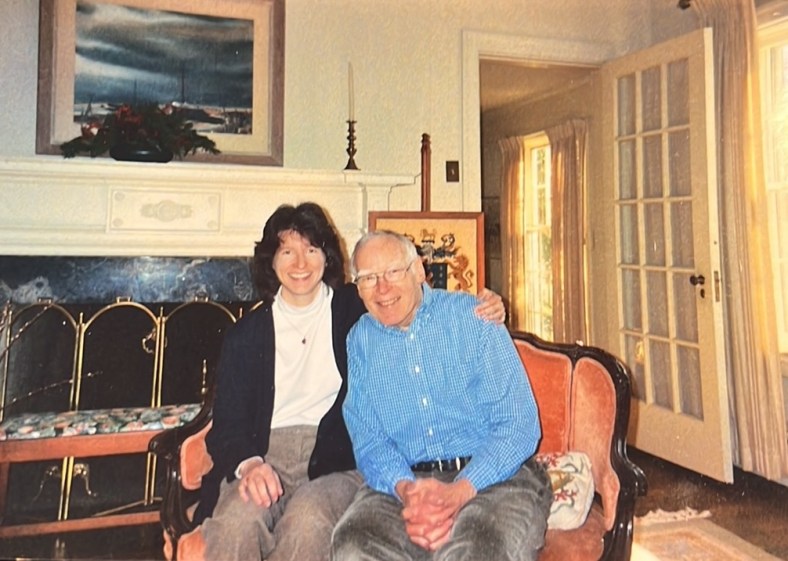

Charles Beaumont Castner Jr. — aka Charlie, or CBC in notes and emails — was retired from a storied public relations career with Louisville & Nashville Railroad (later CSX) by the time we met in 1994. We both worked with Religious Leaders for Fairness, which advocated passage of Louisville’s Fairness Amendment to protect LGBTQ rights.

Charlie was a seasoned Second Presbyterian Church elder and PFLAG dad. I was a twenty-something student at Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, had just lost my father and was trying to figure out a ministry without a clear path.

The Presbyterian Church (USA) at that time was in the midst of study and dialogue on what to do with gay folk — to ordain, welcome or continue with “don’t ask, don’t tell.” Though single at the time, I knew I couldn’t ask a partner to stay in a secretive corner of my life. What was a theologically educated journalist to do?

Charlie and I became fast friends. He’d become an advocate for LGBTQ inclusion when his daughter Louisa came out, and we shared a vocation in storytelling. Along with writing about railroads and organizing tons of train documents, Charlie edited the Louisville Presbytery Pipeline, news of all the PCUSA churches in the Louisville area. It was part of the Synod of Living Waters newspaper covering all things Presbyterian in several Southern states. He was ready to scale back on that, and I became his co-editor with the plan of eventually taking over for him.

We went to monthly communications committee meetings. We covered presbytery meetings, which were all-day affairs with a meal, a worship service and scads of handouts. Then there were all the other events that called for photos and copy … bluegrass gospel quintets, food drives, forums, fellowship with a family of new Bosnian immigrants and more. Some of these took us to the outer reaches of the presbytery, and Charlie and I had great talks on the way.

To him I was not an issue; I was just me. Questions around LGBTQ inclusion were tough for church and society, but to Charlie, a way forward was possible with faith, constructive conversation and goodwill. He’d tell you that shared music — hymns sung in the church choir, boogie-woogie piano jams and more — helped too.

My work with Charlie, and the connections made through him, helped me reshape my career into writing and editing for church-based publications and organizations. Eventually I began doing communications and healing work with animals, too. You just never know where God’s call will lead. It’s never been the pastoral ministry I initially planned, but Charlie helped me see what was possible and craft something even better.

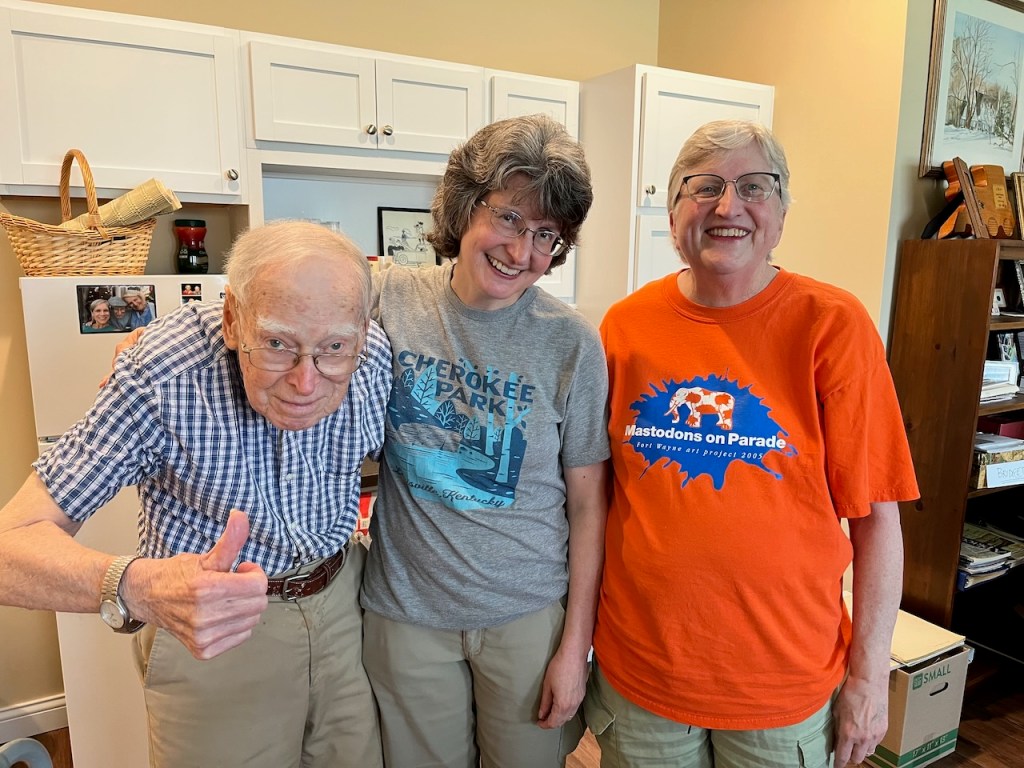

Charlie and his wife Katie remained my Louisville parents after I graduated from seminary and moved back to Indiana. Over the decades I’ve been blessed to know their adult children as well: Beau, Louisa and Fenner, all smart and musical.

Charlie and Katie sold their classic Indian Hills house and moved into a nearby Episcopal Church Home apartment; the Presbyterians were taking over, he jokingly warned his new friends.

Music lifted and powered Charlie through Katie’s passing, recovery from a stroke and a move to assisted living. Getting around with a walker slowed him down, but gave him more time to greet people in the halls. Everybody knew Charlie, and a whole lot of folks are missing him since he passed into the eternal Feb. 3 at age 97.

Somewhere, I’ll bet he’s sprinting after another train.

When Fred Rogers was about halfway through his studies at

When Fred Rogers was about halfway through his studies at